Vera Szekeres-Varsa

Vera Szekeres-Varsa was born in 1933 in Budapest, the second child to a long-ago assimilated Jewish family with no religious beliefs and vivid Hungarian sentiments. In 1944, when the Germans marched in Vera's life changed drastically.

Interviewed by

Mihály Andor

Year of interview

2007

Interview location

Budapest, Hungary

Family background

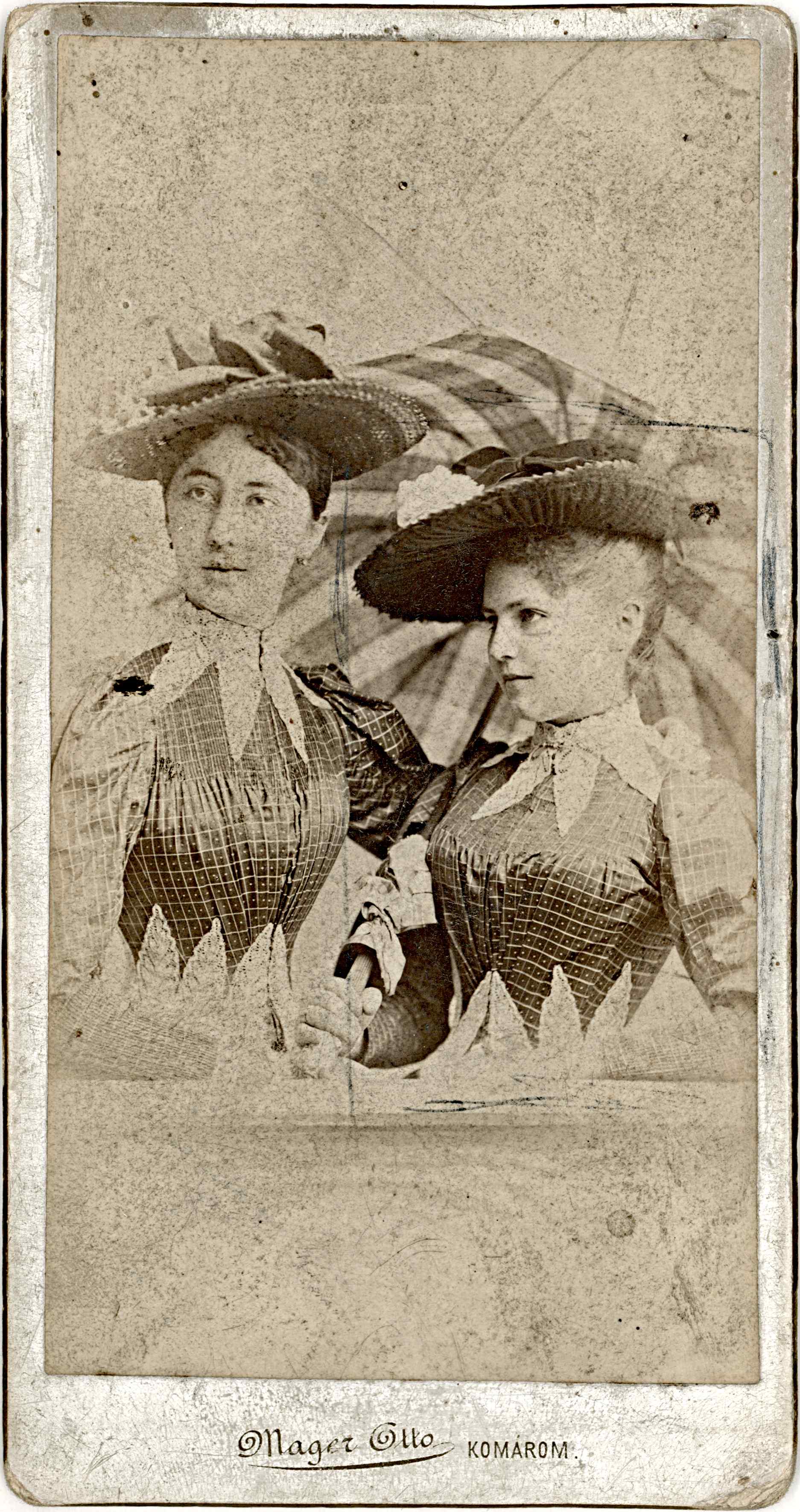

One of my maternal great-grandfathers, Ármin Weisz, was a wholesale dealer in agricultural products in Komárom (Komarno). There is a picture of him in the festive garb of Hungarian noblemen, with a sword at his side. He was a well-to-do man, On the 19th of March 1944, when the Germans marched in, Ármin Weisz hanged himself. He had five children. Ernő became a banker and was a wealthy man, he and his wife spent his vacations in Abbazia, and visited the Opera in Vienna. Blanka married a Jewish forest- and lumberyard owner in Transylvania. Oszkár, who was not educated as a gentleman, became a printer and died young. Then, Aunt Mariska, a granny-like figure to me, and Gizella, my grandmother. She was born in 1871 in Komárom and died in 1921 in Törökbecse (Novi Bece) in Vojvodina.

Maternal grandmother of Vera Szekeres-Varsa

My grandmother was brought up as a noble lady with a mademoiselle by her side. In 1890, she married Izsó Garai, who was called Grünhut before assimilating his name to a more Hungarian version. My great-grandfather, Miksa Grünhut, was a wealthy agricultural estate manager. His son, Izsó, inherited the post on the farm and was later appointed director of a big postal savings bank. They had two children: my mother Ilona (1892-1972) and later my uncle Laci. Laci was shot dead in 1942, blamed for being a partisan liaison. Before my mother's death, she said, "Seeing how things turned out, I wish Laci had truly been a partisan."

My mother grew up well-off and happy. She had a nursery, a piano, and a fräulein from Berlin. They were not religious; neither were they hostile to religion. She went to a public grade school and then to a private boarding school for young ladies. Her report card said she was an Israelite, but I heard nothing of her attending the synagogue. She learned to play the piano and studied Schiller and Goethe.

The mother of Vera Szekeres-Varsa

She was reluctant to marry and finally said yes to the tenth suitor, Vilmos Engel. Vilmos was a journalist and co-owned the local paper Szegedi Napló. After their marriage they settled in Szeged, but in 1925 Vilmos was appointed head of the Rome branch of one of the most prestigious printing houses, the Athéneum. Still, they came back in six months, for my mother was already in love with my father. My mother moved to Pest in 1927. She and Vilmos remained on good terms throughout, and my father did as well. My mother opened a lingerie shop in her apartment in Budapest under the name of Mrs. Engel. My father had already been living in Pest. Meanwhile, in 1928, my sister Klárika was born, and in 1932, they finally married.

Fewer memories endure of the paternal branch. My great-grandfather, Ferenc Weisz, was married to Erzsébet Lechner. He farmed two or three acres of land and probably did some trading. Farkas Weisz, his son, was my grandfather. He had a brother and a sister whose names I don't know. My other great-grandfather, Áron Kesztenbaum, married a convert, Erzsébet Molnár. Farkas was drafted in 1865 but defected and showed up only after the reconciliation with Austria. He became a wagoner. They lived humbly in a house with a dirt floor. Farkas was anti-Habsburg and militantly anti-religious. His wife, Erzsébet Kesztenbaum was a kind of neophyte, the only religious member of the family. They raised four children: a daughter and three sons. The three sons changed their names, assimilating it from Weisz to Varsa. Aunt Róza was the eldest child; she raised two sons; the eldest, Alfred, became a famous doctor in Paris.

The Varsa brothers

The three Varsa boys were Imre, nineteen years older than my father, then Dezső, and finally, my father, József. Uncle Dezső married a Christian woman, Erzsébet Bogdánffy. His mother was furious, making my father swear he would never marry a Christian girl.

Uncle Dezső covered my father's education. My father compromised on his desires to become a history teacher and aimed for a cheaper degree. This is how he became a lawyer. He also pursued sports; they even considered sending him to the 1916 Olympics, but the war intervened. In 1915, he was shot in the lungs on the Eastern Front and contracted tuberculosis in the trenches. He was captured and sent to Siberia. Returning home, he enrolled in the Faculty of Humanities but dropped out immediately because the Jew beatings in universities had just begun. He passed the bar exam in Szeged and started to work in a bank.

Childhood

Szekeres-Varsa Vera at the age of 3

My father moved to Budapest, where he opened a law office. Soon, my mother arrived as well. In 1928, my sister Klárika was born. They married in 1932 and moved in together at last. For a long time, they looked for an ideal dwelling place, and in 1935, they ended up in the Phőnix House, in a popular bourgeois part of Budapest, Újlipótváros. I only moved out in 1979. Meanwhile, the law firm was pretty successful. I was three years old when my sister died of tuberculosis. Incidentally, there was a period when I also suffered from tuberculosis and, simultaneously, whooping cough. My father became temporarily religious after my sister's death, though he had had no religious sentiment before. Then, after three years or so, his religiosity faded, parallel with the growing Nazi influence. I started school in 1939. I went to a private school with four pupils in a class. Looking back, eighty percent of the children were Jewish.

Vera Szekeres-Varsa

I finished elementary school in 1943, and in the autumn of 1943, a Jewish girl did not have many choices. There were two options: a civil or Jewish school; I went to the Jewish one for health reasons. Soon, I could no longer take my Hebrew-letter prayer books to school.

The Holocaust in Budapest

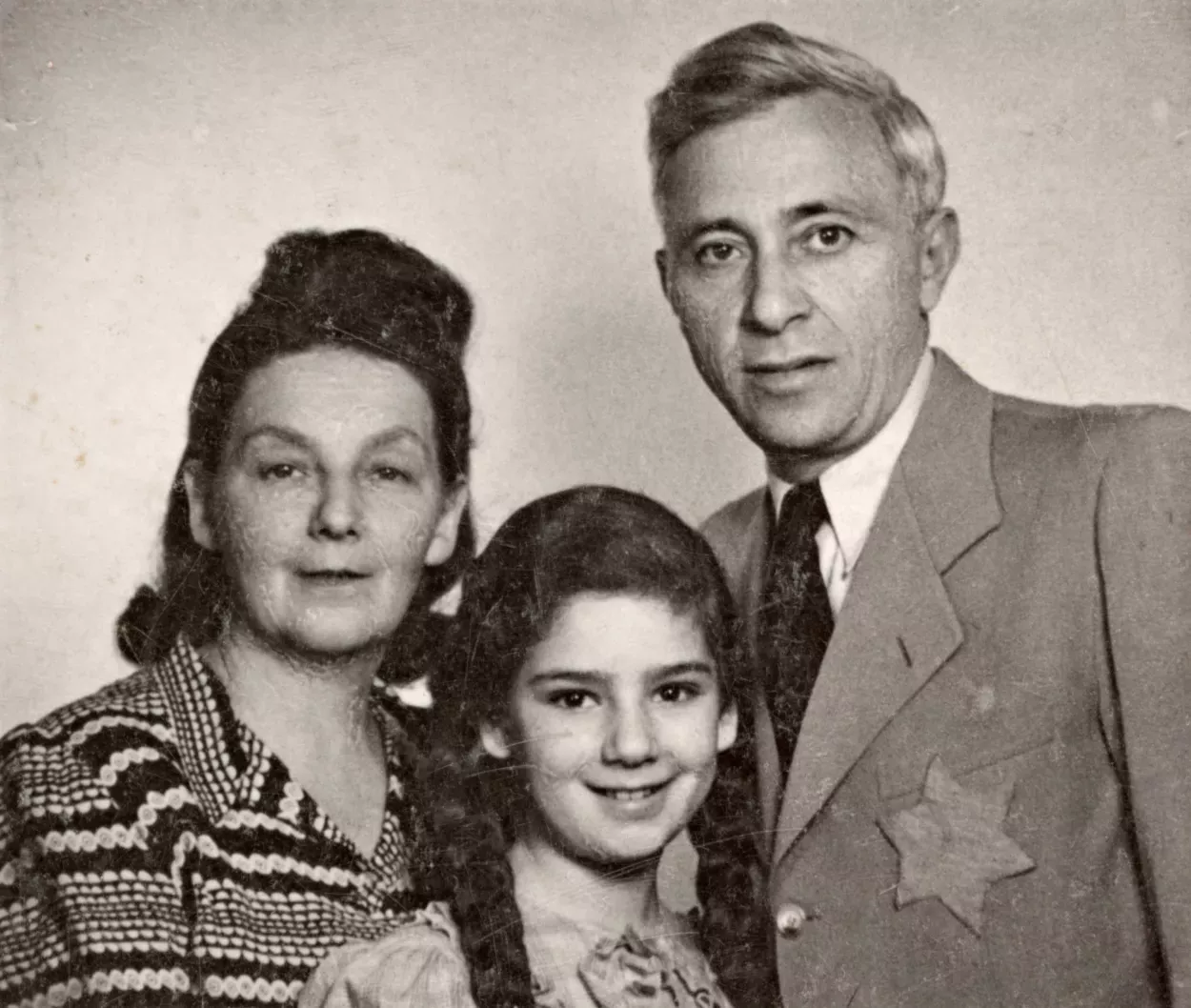

I never endured any antisemitic incidents until 1944. Now Mariska, my mother’s helper, was cleaning behind closed blinds because it was forbidden to have a Christian employee. At that point, Uncle Dezső was not considered Jewish by law, so he took over the business. A stooge led Vilmos's little printing shop, one of the printers. I remember my parents' shock when the Germans marched in on March 19, 1944. In April, the anti-Jewish law disbarred my father because he was Jewish. In May, we had to move to a so-called yellow star house designated for Jews. Soon, thirty-five of us lived in the flat, and I was sleeping under the piano with another little girl. We decided to be baptized in 1944. We bought fake documents; my new name was Veronika Vágner. No money was accepted for the papers, objects were demanded instead: for example, my gramophone and bicycle. We had four Schutzpasses

Vera Szekeres-Varsa with her parents

On October 15, 1944, when the Arrow Cross

A few days later, my seriously ill father was drafted for slave labour. My mother and Uncle Dezső had set up a plan to rescue him. I remember the rehearsal of the “performance” of buying him out. That's how my father came home. In the yellow star house, parents organised schooling. They taught what they could, and some excellent teachers in the building joined them. It was difficult to manage cooking family after family, so we decided to cook collectively. Three women cooked one day, three other women the next day, and we ate simultaneously. Each spoonful of food was carefully allotted. On the day of Horthy's proclamation

We soon had an apartment to stay in. It so happened that the Christian wife of one of Uncle Dezső's sons, Sárika, was related to a high-ranking army doctor, whose commanders posted him outside Budapest, and his wife went with him. She gave the apartment key to Sárika, who gave it to us. It was a large apartment in the city center in an elegant residential building. We had already obtained our false papers; we were a Lutheran refugee family, Vágner. And it turned out that the maiden name of the flat's owner was Mária Wagner. We told the concierge that Mária was my father's cousin. We found three leeks in the kitchen; my father told us the three leeks had to last three days. We rarely left the house. On the streets, my mother would hide my two big red pigtails under my coat because red hair was characteristic.

We were liberated on January 17. The Russian soldiers stormed into our shelter, looking for “nemetzki fascisti,” meaning Germans or armed Arrow Cross cadres, but as all was still and the cellar was not crowded, they set up their radio post there. I wish to mention one more terrible incident. After the Russians marched in, I gave up an evil Arrow Cross officer to the Russians. They shot him dead on the spot before my eyes. After a week or two, we returned to the Phoenix House, our home. Transylvanian refugees lived in our apartment in the Phoenix House but left peacefully. At home, I developed an extreme fever for two days; the stress of the previous months must have knocked me out.

After the war: education, ideology, marriages and work

School started in March. We didn't want to learn German, so we went on strike and got an English teacher. I became an Anglomaniac for a while. In 1947, I told my mother I didn't want to go to Jewish High School anymore, because everyone there was Zionist. She was happy that I didn't want to go to Palestine. I enrolled at Varga Katalin High School. At that time, I was already over my Anglomania and more interested in communism. At the Varga Katalin High School, the girls took French and dance courses while I pondered the world revolution. And then, I met a primary school friend at the swimming pool (I had a swimming pass because health came first) and asked which school she attended. She told me she went to the one on Szemere Street. I asked her how the school was, and she said it was good; I wondered how the DISZ (Union of Working Youth )

While all this was happening to me, my father re-entered the bar association, and his law firm was up and running again. Forced labour, life in the cellar, and constant fear deteriorated his health. Despite being one of the first persons in Europe to receive streptomycin

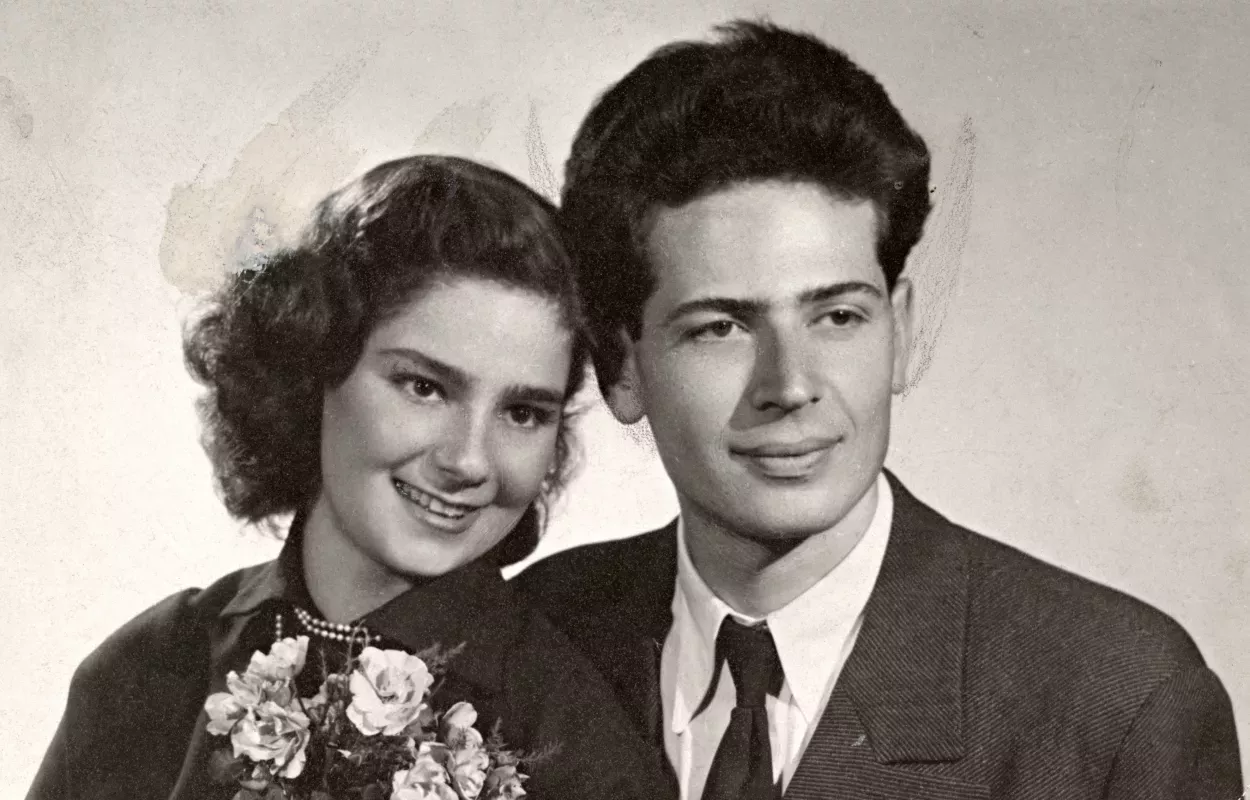

I married my teenage sweetheart and got pregnant soon. He was accepted to medical school, but in September, he was offered a Soviet scholarship. Such things were not to be refused. We agreed that I would wait for him. I had a bad pregnancy. I walked a lot, as walking was considered good for my health, and my faithful walking companion was György Konrád. He was expelled from university for concealing that his father employed several people in his hardware store during the peak season. My daughter Judit was born in April 1953, on my twentieth birthday. The first time her father saw her, she was six weeks old.

Interestingly, a statement from Stalin himself awoke my doubt. Stalin said that Mayakovsky was the greatest poet who ever lived and ever would live. I believed the first half, but the second made me wonder. How can you tell that in advance? Food stamps didn't bother me, but deportation did. I knew people who were deported, and I knew they could not have been exploiters. And people were just thrown out of their homes for no good reason. It was only in 1955 that I woke up fully. Until then, I believed the whole thing, not just me, but people smarter than me, like Konrád. Then, in 1956, came the Khrushchev speech, from which we could learn a few things. By then, we had become ardent supporters of Imre Nagy

Pregnancy prevented me from attending university lectures, but I took my exams, and my mother helped me with the child. It never came to my mind to do anything else but study at the university. And then, I unexpectedly failed the Theory of Literary Translation exam. I got a "B" on my literary translation paper, but the grade was crossed in red on my report card and marked "invalid." The head of Admission whispered into my ear that a comrade didn't want me to be there, and she advised me to transfer to the teacher training course. I never found out what this comrade's problem was with me. Maybe, I was a little out of line. Because we were destitute, I wore awful rags, but I had a colourful scarf whose corner I wore out of the buttonhole. This extravagance was the subject of a DISZ meeting. I finally graduated as a teacher in 1955. I divorced my first husband in 1955, but we split up a year earlier. I married György Konrád right away.

Vera Szekeres-Varsa with György Konrád

After graduating from university, I was placed in a primary school. I taught Russian, English, and Hungarian there for six years. I started teaching in a junior high school. At first, I was not too fond of it because the headmistress was a hag. Again, I had a scarf issue. I wore a tiny scarf, a kitty scarf in Hungarian. The headmistress asked me what it was, and I told her. “We're not kittens; we're teachers”, she replied. And that's how it started; from then on, she vexed me for everything. After six years, I left and began teaching at Trefort High School.

The marriage with György Konrád lasted seven years. Shortly after we separated, I got married to György Szekeres. György Szekeres studied at the Sorbonne, and when the war broke out, he volunteered. He got involved in the French resistance movement. He served as commander of all the foreign fighters in the partisan army, came home in 1945, and became a journalist and then a diplomat. He would have liked to leave the political scene, but he was caught in the web of political games of the 50’s and the paranoia of the international communist movement. He was arrested and served five years in Rákosi Mátyás’

In the meantime, I graduated with a degree in psychology. I wanted to be a psychologist in my childhood, but when I went to university, it was declared a bourgeois pseudoscience. When I started teaching, I felt I needed psychology to do my job. In 1965, I received an album from the Cairo Museum and fell in love with Egyptian art. So, in 1968, I started a course in art history on an individual correspondence basis.

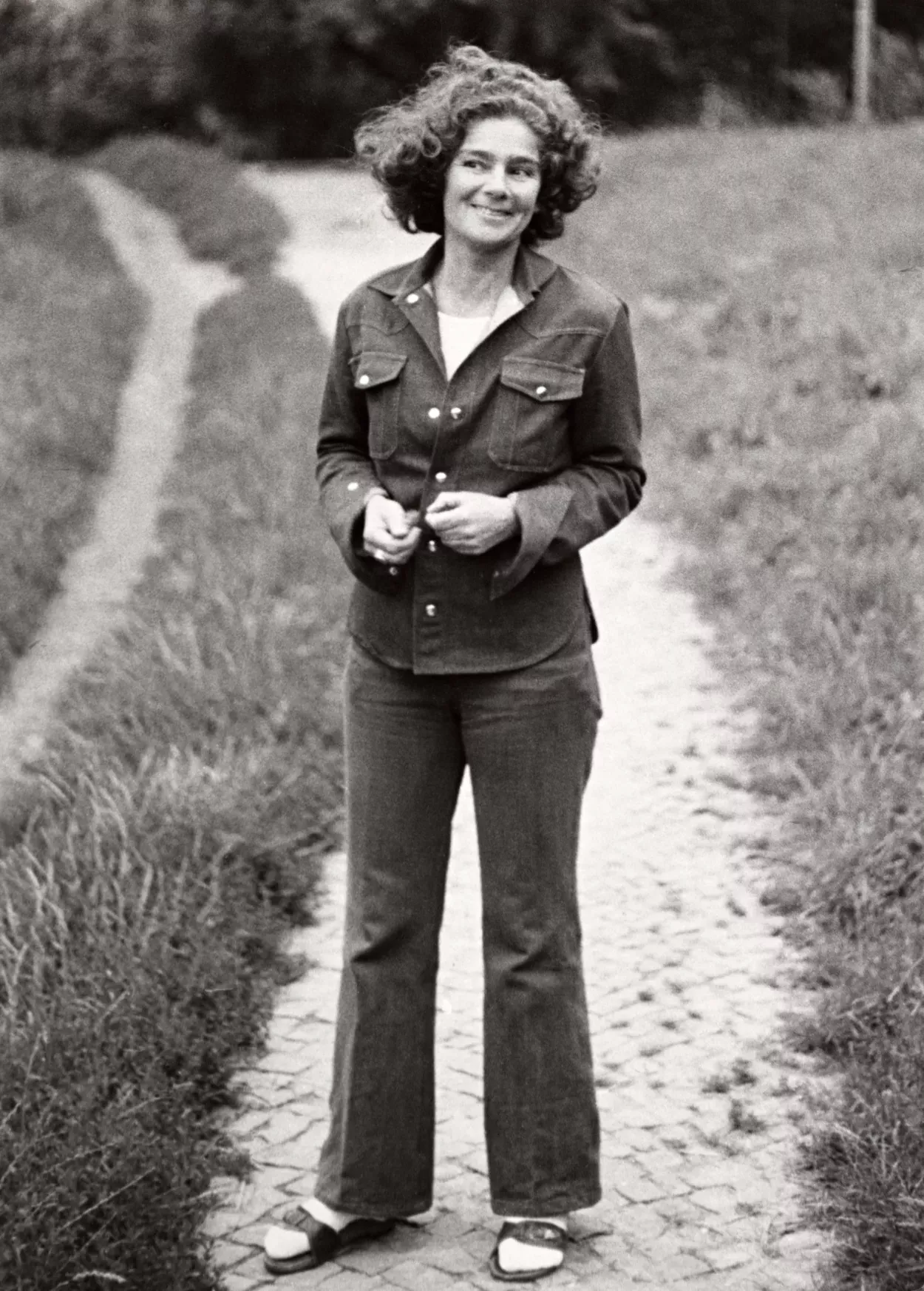

Vera Szekeres-Varsa

Then, by a rather unfortunate string of events, something good happened. In 1974, I met András Román, whom I had not seen for twenty-five or thirty years. The first time I met him was in 1946; I sat on a bench in the street waiting for my mother, and I was reading, as always. An auntie sat next to me, we chatted, and she promised her son would teach me to dance. He was András Román, for whom I was the girl sitting on a bench, reading. He was an excellent art historian and a wonderful man. He was responsible for reconstructing several beautiful villages and buildings, including the synagogue in Mád. The Mád restoration was awarded the Europa Nostra prize. After the change of the regime, when it became possible to buy the flat we were living in, András and I decided to get married. I insisted that Zsófi, my granddaughter, be my bridesmaid. In 2005, after five bitter years of illness and eight operations, András succumbed, and he died in his bed in the apartment where he was born. While I was head teacher at Trefort, I worked as a lecturer at the Academy of Drama and Film from 1974. In 1979, I became a full professor there, and so I finished my career as a high school teacher.

Democratic transformation and family

Although all my movement activities ceased after 1956, their spell continued to haunt me. In 1988, I attended the formation meeting of the Social Democratic Party. Then I checked out the Hungarian October Party, but it was clear that this far-left party was not for me, either. And then, I joined the Alliance of Free Democrats, SZDSZ, the liberal party. I've been a member of the SZDSZ ever since

Vera Szekeres-Varsa at the opening of the Poetry Day

For several years, I was head of Amnesty International’s Hungarian branch. I raised my daughter alone; my mother helped me raise her. I didn't have a model or an idea of child-rearing; I was too young, and everything was very different from how I was raised. But I solved the task; after all, I am a teacher. She graduated with honours from the Faculty of Humanities in French and Russian languages, later in Art History. After the regime change, she founded a successful private gallery. She has three daughters; may they all live in peace. My daughter considers herself Jewish but is entirely non-religious. It is easier to be non-Jewish than Jewish. I didn't raise her as a Jew; not even my ancestors were religious. Still, the next generation should know about the persecution because they should learn that all persecution should be stopped by the most potent means at the very first moment. My attitude toward Israel is biased. Come what may, this state must live, flourish, and be strong. I first visited Israel in 1988, then eight more times, lately in 2006.