Rosa Rosenstein

Rosa Rosenstein was born in Berlin in 1907 to a Jewish family. Rosa worked in her father's tailor shop. She was married and had two children. Together with her family she fled from National Socialist persecution to Budapest, where she survived the war.

Centropa has made a documentary film about Rosa Rosenstein in 2012. (Available with German narration and English or Hebrew subtitles.)

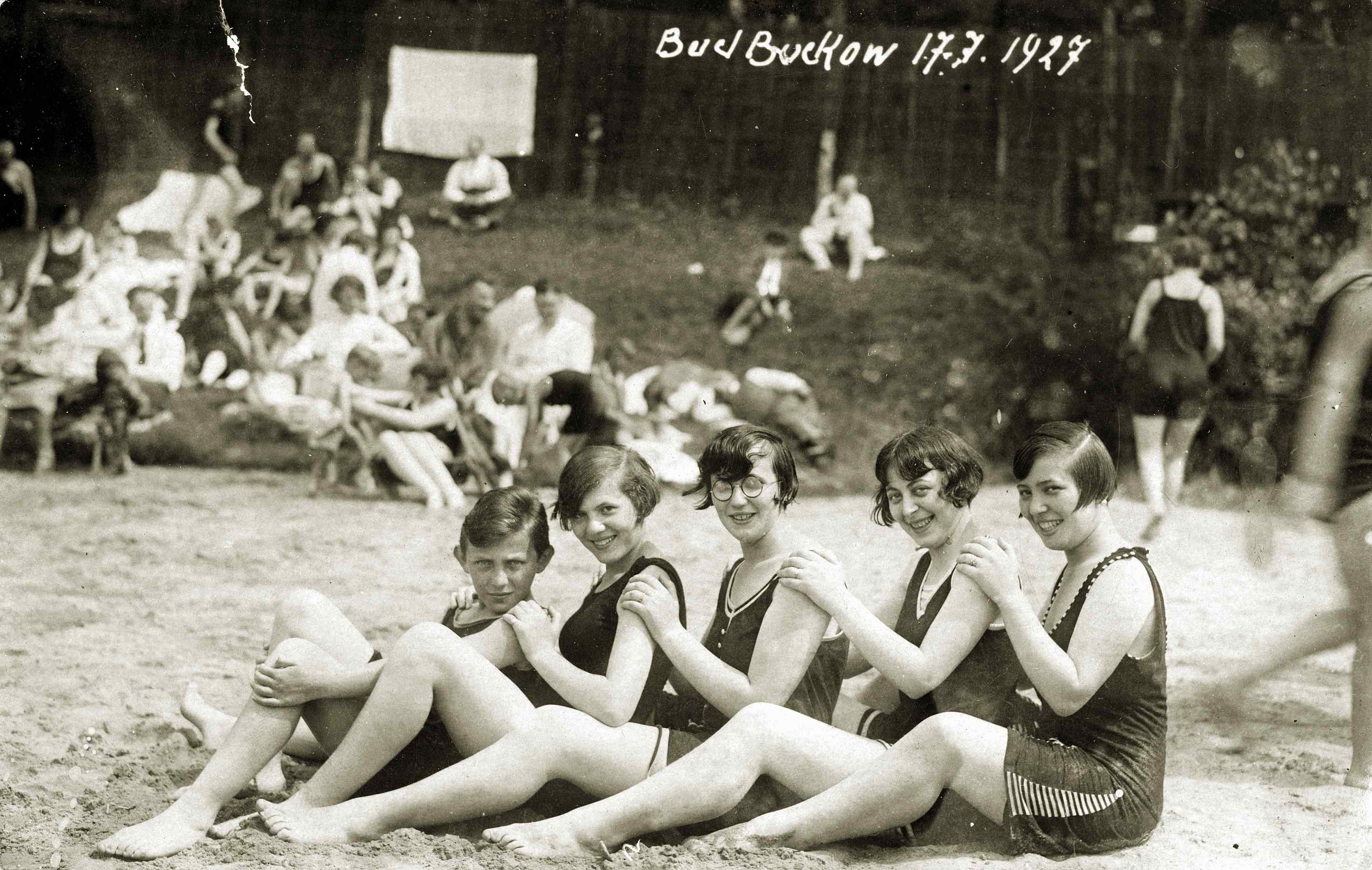

Rosa Rosenstein with her siblings Betty, Erna, Cilly and Anschel

Childhood

My grandparents and my parents were born in Galicia. My family on my father’s side was called Braw. My grandmother, Rivka Finder, née Braw, died before I was born. I was named after her, Rosa in German and Rivka in Yiddish. My father was a tailor and worked from home. In later years, we had a menswear wholesale and retail store. My father wasn’t drafted into the army during WWI; he was given his medicals four times during World War I but was deferred every single time because he had horrible varicose veins. And that made him fortunate. He was at home and could take care of us. He drove to the farmers and got food for us, so we wouldn’t starve. My mother was good at everything, too. We never went hungry.

My parents were foreigners in Germany. I’ve had three nationalities, but I was never German. At the time I was born in Berlin, I was Austrian. I was born in 1907, but Poland was only founded in 1922.

My mother was engaged to my father for a very long time. It was an arranged marriage. My sister Betty came after me in 1909. Erna, born in 1911, was the third, and Cilly, born in 1913, was the youngest sister. My brother Arthur, Anschel in Yiddish, was the youngest. All of us five siblings are very close. Sure, we all had different opinions, but we never really had a row with each other. And that only happens in a few families.

Rosa Rosenstein with her siblings Betty, Erna, Cilly and Anschel in Bad Buckow

In Berlin, we lived in a large four-room apartment on Templiner Strasse.

I didn’t care about clothes at all. At Rosh Hashanah,

My father prepared our breakfast, which we took along to school. We had everything, you know. Berlin has wonderful lakes. On Wednesday we always went out in paddle boats, and we also went canoeing. We had delicious food, bought the very best. We didn’t lack anything. My father did everything for his daughters. My mother was a bookworm just like me. She only went to school for a year in Galicia, while her seven brothers all studied. Grandfather always said it was enough for a girl to be able to write her name and know how to bake bread and make butter. But my mother taught herself how to read and write. We had a real library at home. When we emigrated after Hitler’s rise to power, my heart bled because we had to leave all our books behind.

Rosa Rosenstein at a Purim party

Education and work

I went to a Jewish girls’ school. I had no contact whatsoever with Christians. My parents didn’t either, only business-wise, but privately, they didn’t. However, I did have a Christian girlfriend when I was young; she lived in the same building, and I went along when she went to confession.

I then had to leave school. I was told what to do: It was decided how long I was allowed to go to school, and then I had to switch to a business academy because my father needed me in the shop. At this business academy, you had to learn everything in half a year: typewriting, stenography, accounting, and all that at a great speed. I had classmates who were 20 years old, while I was only 15, but I was much better than the others.

In my father’s business, we made and sold men’s ready-made clothes ourselves. For a while, we had our own retail stores: one was on Hermannstrasse in Neukölln, the other one on Klosterstrasse.

Marriage

I lived at home until my wedding day. My first husband was also a tailor, but above all he was a Hungarian. Oh, he certainly was a handsome young man! I was working at my father’s, in a factory building with large windows. My desk stood at the window. On the opposite side there was a men’s ready-made clothes factory, and there was this good-looking man sitting at the sewing-machine. We kept smiling at each other. I didn’t know who he was; he didn’t know who I was. One day a messenger came up with a big box filled with candies and said, ‘This is from the young man across the way.’ That’s how it all started. I accepted the gift, of course, and said thank you. I was not yet 18, but I was happy, and why not?

One day I went home earlier. I had been in the shop and walked via Hackescher Markt to a large bookstore on Rosenthalerstrasse. So I’m standing there, looking at the books and all of a sudden I hear a voice behind me, slowly saying, ‘Isn’t that beautiful?’ I turned around, and there he stood. He asked if he could walk me home since he was going the same way. So I said, “If you please.” After that he sometimes accompanied me on my way, and then he started inviting me. That was always on a Saturday evening; one didn’t have time during the week, of course. Our meeting place was at the underground station on the corner of Schönhauser Allee and Schwedterstrasse. I dressed, got ready, and I also went to the hairdresser’s. My parents knew that I had a rendezvous, and my mother told me, ‘Come on, hurry now, you’re going to be far too late.’ And I replied, ‘If he’s really interested, he will wait.’ So I went down to the underground station, and there was no one there. Then, after five minutes or so, I saw him come running, completely out of breath. What happened? Well, I apologized for being late. He, however, thought that I was waiting at the other station, so he had to run to the next station and back. We went to a restaurant called ‘Schottenhamel,’ a very elegant restaurant, but I was kosher. He ordered a meat platter, while I had coffee and cake, as I didn’t eat treyf

Rosa and Michi Weisz's wedding

Well, then we got married. I insisted on the temple on Oranienburger Strasse because it was the most beautiful temple in Berlin, and, it was even said, the most beautiful one in all Europe. After the ceremony, we went for a meal at a restaurant on Kupfergraben. The plan was to dance after the meal; after all, there were a lot of young people there. But the music was horrible. My girlfriend’s brother was a wonderful pianist and could play anything by heart; he could play without sheet music. So he sat down at the piano and started to play, and then we were able to dance properly.

When our daughter Bessy was born in 1929, my husband and I were both still very young, but fortunately I had my parents to help us. In 1933, my second daughter, Lilly, came into the world. And I didn’t want that, I only wanted to have one child. Back then, it was popular to only have one child. My husband’s sister wanted to help me. She told me I should drink tea, sit in hot water and jump from the table, but nothing helped. Finally I told my mother that I was pregnant and she did not mince words: ‘What is that? Don’t do it! What’s another child? Why don’t you want to have it? The age difference is just right!’ But the worst thing was that she told my daughter about this once she had grown up. And from then on my daughter always told me, ‘You didn’t want to have me.’

Persecution and flight

My siblings Erna, Betty and Anschi went to Palestine in the beginning of the 1930s. My father was arrested in 1938, immediately after “Kristallnacht”,

Three weeks after the outbreak of the war, you had to black out your apartment, and food ration cards were introduced. Of course, Jews got less. Apart from that, we could only go shopping at certain hours and not during the whole day. My husband said, ‘Nothing can happen to us in Hungary.’ So then we packed our suitcases and went to Budapest, because my husband claimed in Budapest nothing would ever happen. However, to be on the safe side, I had organized entry permits to Palestine for my children.

The Jews in Hungary still lived a good life. At that time, many Jews lived in Budapest, I think around 200,000. ‘Stay in Hungary,’ my parents wrote. Back then you could only enter Palestine if you had a certificate stating that your profession was needed in the country. And this certificate included a capital of so many thousand British pounds. My parents wrote to us, saying that the capital would be deposited for us in Holland. Much to our misfortune, though, the Germans invaded Holland.

Rosa Rosenstein with her daughters

One day, they arrested me and took me and my children to an internment camp. My husband was separated from us in the men’s part of the camp. I still had the exit permits for my children. I always wrote Red Cross letters – via my cousin in Argentina, who forwarded them – and thus we were still in touch with my family in Palestine. After our arrest, my brother-in-law wrote from Palestine: ‘Send the children, please send the children. We will raise them as if they were our own.’ The Jewish community in Budapest organized it all. Lilly didn’t want to leave; she was eight, and Bessy was eleven when they left. In the end, they agreed, but the younger one told me that her sister had beaten her until she said ‘yes.’ This way, she saved her life.

I was allowed to accompany the children from the camp to the train station in Budapest. My husband, who was in the men’s internment camp, was only allowed to take them to the bus stop. That’s where he said goodbye to them. And that was the last time they saw their father. Lilly was standing at the window with tears running down her face. They went to Bulgaria by train, then crossed over into Turkey by ship and from there, went by bus via Syria to Palestine. My parents welcomed them in Palestine.

On my husband’s death notification it said: cardiac arrest. I was told later that he’d died of spotted fever. He was sent to Russia, to Kiev,

Then came the year 1944. Adolf Eichmann

We were suddenly called into the building, the women separately. An officer sat there, writing down our names. He looked at me, then looked at the death notification, then looked at me again and said in German, ‘You are an Israelite?’ I said, ‘Yes.’ Then we were taken into a huge room, and there were some 400 women again. We were locked up, and by that night Budapest had already been bombed: at daytime by the Americans and the British, at nighttime by the Russians. The women prayed for the next bomb to hit us. For, you know, we expected the worst, the very worst. We were in there for four days. The men were deported, that we knew. But they didn’t know where to take the 400 women. They didn’t have trains. That was our great fortune. When they released us, we had to give them our addresses, and I was afraid to return to my room. But we had a Viennese friend in Budapest, a widow. When she opened the door for me, she couldn’t believe her eyes: ‘Resi, you are alive?’ This is where I met my future husband, Alfred Rosenstein, whom I knew from the camp. He was from Vienna and so charming; the women were crazy about him.

Rosa and Alfred Rosenstein with their son

We had a mutual acquaintance who had bought false papers a few months earlier. He bribed the janitor of a villa and we, nine of us, were then hiding from the mass deportations in one room of that villa. In the end, when it was all over, when we were already dancing in the streets, 60 Jews suddenly appeared from the villa next door - the janitor had been hiding them in return for money and jewelry, in coal cellars and what not. This is why I said, in Budapest you could get anything, if you had money.

I knew I was pregnant and I said to myself: either the child will perish with me, or I do something. And Alfred said, ‘You won’t do anything. If we survive, we will have a child.’ But I went to see the doctor in the ghetto anyway.

One day, we were lying in the room wearing our coats – there were no windows any more – and all of a sudden I heard a voice speaking into a megaphone: ‘This is the Russian Army. People of Budapest, wait! We will liberate you.’ That’s what they said in German, Hungarian and Russian. And so we waited. One fine day, it was a Sunday, I was standing at the window, there was a deathly silence, and I saw a Russian with a fur hat and machine-gun coming through the garden towards the house. I said, ‘There’s a Russian here.’ My girlfriend said, ‘The first Russian horse I see – I will kiss its behind.’

Post-war

After the liberation, I first stayed in Hungary. I didn’t want to go to Austria; I wanted to move to my children and parents in Israel. But my husband said that he didn’t have a proper profession to go to Israel. He was a businessman and worked for his brother, who owned a large oil company. He worked as a salesman. That wasn’t the right profession for Israel. He wanted to go to Austria to put in a claim for reparation payment and get the money so we could immigrate to Israel.

Before the war, my husband’s sisters had a restaurant called ‘Grill am Peter’ in Vienna, which was Aryanized.

I went to Israel for the first time in 1949 with my son. My daughter Bessy went to the Israeli army, later she worked for the city council, taking care of elderly people. Lilly came to live with me in Vienna for a year. She had gone to school in Israel, but, of course, she could speak German. My mother never learned Hebrew. I never saw my father again, that was terrible. My son moved to Israel after high school. That was shortly after my husband’s death in 1961.

Rosa in Israel with her grandchildren

I didn’t like the Austrians. I always regarded them as Nazis. Once, at the beginning of the 1950s, I spent two months in Israel. When I came back to Vienna and went to my local baker to buy bread, the baker’s wife asked me, ‘Mrs. Rosenstein, where have you been for so long?’ I said, ‘I was in Israel.’ And she looked at me and said, ‘You’re Jewish? You don’t look Jewish!’ Upon which I said, ‘Why, Mrs. Schubert? Because I don’t have horns on my head?’ And she said, ‘For Goodness sake, no, I didn’t mean it like that. We had a supplier, a Jew who supplied flour, and he was a decent person, too.’ That was at the beginning of the 1950s. Nothing much has changed over the years. Haider and Stadler,

Rosa Rosenstein in her Vienna apartment, 1990s

In Germany, I didn’t feel any antisemitism. I was laughing and joking around with Christian laborers in my father’s workshop. Many of them also knew when our holidays were. I went to Berlin with my sister; back then it was still divided into East and West Berlin.